Hemp

Not Quite So Sweet: Hemp & the Honeybee

Recent reports have argued that hemp may be able to help struggling honeybee populations. But over a decade after news of their decline first broke, what’s hurting the pollinating powerhouses remains complicated.

A funny thing happened in November 2006.

David Hackenberg, a Pennsylvania beekeeper tending to his hives in Florida, went on a routine check. What he found was startling: After opening up his hives, he discovered that there were very few honeybees present, which was an abnormality. He checked around the hives, but couldn’t find any perished bees — another abnormality.

Hackenberg’s discovery alerted beekeepers in the United States of a serious — and potentially catastrophic — problem that was later named colony collapse disorder (CCD). But the phenomenon wasn’t entirely new. It had happened sporadically throughout history, though in Europe in the mid-1990s it had started to occur with startling frequency.

But somehow, news of what was happening in Europe had been largely ignored, until U.S. beekeepers like Hackenberg reported their colonies were collapsing too. Once the problem was on U.S. soil, it was finally considered a problem. Print and television media quickly picked up the story. Alarm bells rang.

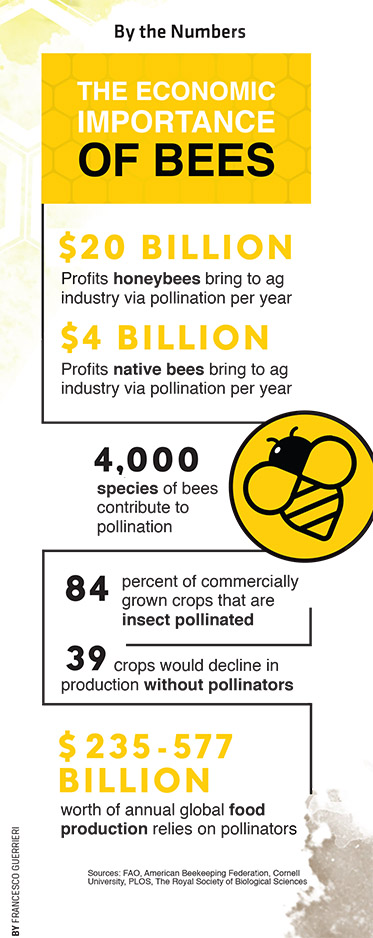

The American public soon found out that honeybees, apart from simply creating something delicious, are important. As in our entire food production system is dependent on them important. The American Beekeeping Federation estimates that honeybees contribute $20 billion to the value of U.S. agriculture annually through increased yields and superior-quality harvests. And if they did in fact disappear, we’d be, well, up a certain creek without a paddle.

So, a decade later, everything’s okay, right?

Well, the rapid decline of the honeybee has forced us to pay attention. Researchers and beekeepers are searching for solutions — sometimes finding answers, sometimes more questions.

What they’ve found paints a complicated picture of what’s affecting honeybees. The fate of the honeybee may be tied to the way in which we’ve altered our environment to suit the needs of a ballooning human population, as well as diseases and pests that can more effectively target honeybees already suffering from poor health related to habitat loss.

But with knowledge comes the power to act. By reengineering our current environment into one that is healthier for pollinators, we can change the honeybee narrative. Some feel hemp offers an opportunity to help provide a solution. But in order to seize that opportunity, we need to think about how and what types of hemp we are growing as the money pours into our post-Farm Bill world.

Identifying the Culprit

In the immediate aftermath of the CCD crisis, theories abounded as to what the cause was. Some were the usual ideas put forth in times of uncertainty: a government experiment gone wrong, Russian sabotage, aliens, the rapture.

But the most ardently discussed (and much more plausible) cause for the phenomenon revolved around a class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids. Initially, the amount of evidence supporting their role in CCD was strong enough that several European governments banned specific neonicotinoids thought to be causing CCD.

While individual states have restricted the use of neonicotinoids, on a federal level the U.S. has failed to act in any meaningful way.

“People always ask me, ‘What’s killing the bees?’ I say, ‘It’s not one thing, it’s everything.’” — Nick French

For much of the public, the story of the honeybee ends there: Honeybees are threatened and pesticides are the culprit. In a way, neonicotinoids being the sole culprit would have been a best-case scenario. Eventually, under pressure from an array of lobbying groups and the public at large, we likely could have convinced our representatives to vote against the corporate interests that fund their campaigns.

But as we’ve continued to study CCD, a more complex picture — one that tells the all-too-familiar story of unintended consequences of human-caused ecosystem alteration — has appeared. Yes, neonicotinoids are bad for honeybees. But figuring out what’s causing the plight of the honeybee is, unfortunately, more complicated than simply banning certain pesticides.

“I always talk about bees, birds, bats, and butterflies, because that’s what we’re witnessing, the sixth great extinction right now,” says Nick French, owner of Colorado Hemp Honey. French sells CBD-infused hemp honey and manages about 150 colonies of honeybees on his farm in Douglas County, Colorado.

“There are lots of other species that are dying, but the ones you hear about are the bees,” French continues. “These [different species], they’re all dying off at alarming rates. And it’s a combination of things. People always ask me, ‘What’s killing the bees?’ I say, ‘It’s not one thing, it’s everything.’”

French, like many etymologists studying honeybee and insect population declinations, believes that an intensive combination of human-caused environmental factors is eroding honeybee health in general, and thus their numbers.

Illustrating the issue, French says: “Imagine a six-legged table, where each one of those legs represents a factor affecting bees. One leg is a polluted city environment. Another one is a lack of forage and genetically modified crops. Another one is for mites. Another one might be other diseases that affect bees. Some people say migratory beekeeping is to blame. Well, that table cannot stand if you pull those legs out from under it. In other words, bees cannot evolve fast enough to overcome all these different changes that are happening in the environment.”

It’s Not Just Bees That Are in Trouble

Insects, in general, are disappearing at alarming rates, scientists say.

In a study published in Science Direct in early 2019, Francisco Sánchez-Bayo, an environmental scientist and ecologist at the University of Sydney, and Kris A.G. Wyckhuys, a Belgian bioscience engineer and insect ecologist, wrote about their recent compilation of 73 historical reports detailing insect populations from around the globe.

What they found was shocking. According to the study, over 40% of global insect populations are threatened with extinction over the next few decades. Two recent studies, in particular, have scientists concerned.

Citing a 2017 study, the authors write: “A 27-year-long population monitoring study revealed a shocking 76% decline in flying insect biomass at several of Germany’s protected areas.”

And, summarizing a 2018 study, they state: “[A] recent study in rainforests of Puerto Rico has reported biomass losses between 98% and 78% for ground-foraging and canopy-dwelling arthropods over a 36-year period, with respective annual losses between 2.7% and 2.2%.”

Even if you’re an entomophobe (someone who is scared of all those creepy crawlies), that’s still bad news. Beyond pollination, insects are essential to a host of processes unique to each ecosystem that they thrive in. And many animals rely on insects as their primary or only food source. If we lose all of the insects, it will simply be one wave in a waterfall of disastrous consequences.

Honeybees, at least, have an advantage over most insects. Because they’re so essential to our food systems, we breed and reproduce them to replenish their numbers when they’re threatened. Prior to CCD, beekeepers reported losses of between 15% and 20% annually, per USDA surveys. Over the last decade, that number has roughly doubled. The falling honeybee numbers means that beekeepers are suffering a financial toll, which ripples into higher prices at the supermarket. While this population loss and price jump shouldn’t be shrugged off, beekeepers have at least been able to keep us from a complete species collapse by reproducing honeybees.

So, if we can force honeybee populations to reproduce, why are their numbers still declining?

What Can Exist Without Habitat or Food?

The issues facing honeybees are issues familiar to other insects, says Arathi Seshadri, a professor at Colorado State University who specializes in pollination and plant production.

“One thing is that when we are trying to understand what is going on with honeybees, it actually opens up a broader question,” she says. “The fact is, it’s not just honey bees, it’s actually all pollinators that are experiencing this, because the kinds of challenges that the bees are facing apply to not just this one genus, but across the board apply to a lot of beneficial insects and pollinators that are all dependent on the same kinds of things.”

In particular, Seshadri says pollinators are suffering from a lack of habitat, and subsequently, access to food.

“Wildflowers and other plants are not present anymore, either because we have eliminated them by using herbicides and chemicals, or these areas have become developed into newer agricultural areas, or they have become urbanized areas just because the human population is growing,” she says. “We are just extensively destroying the natural habitat to meet human needs.”

That synopsis aligns with what Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys found. They describe the issues driving insect decline, appearing in order of what they deem importance, as habitat loss as wild areas turn into agricultural and urban land, pollution mostly from synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, diseases, and climate change.

But when it comes to honeybees, both Seshadri and French offer up plenty of hope as a side to go along with the heaps of sobering reality.

Seshadri says that everything from large-scale farming operations diversifying their crops and restoring wildflowers for pollinators to your choices in your backyard can help move the needle in the right way.

“People are becoming aware and there are several different kinds of efforts to improve pollinator habitat,” says Seshadri. “One of the things that we are trying to get across is that people usually end up blaming the chemicals. And it’s not always the chemicals that are to blame.”

She says that by planting native species in your yard, you can both provide food for pollinators and lessen your usage of water, because native plants are adapted to the environment.

Speaking about the prevalence of that idyllic, weed-free Kentucky Bluegrass, Seshadri says homeowners should challenge themselves never to use chemicals in their own backyards. “If you’re in urban areas, in your backyard, do we need chemicals at all?” she asks.

French for his part, says that he’s seen a huge increase in interest for the honeybee in his time as a beekeeper.

“What we’re seeing is that more people are getting interested in hobby beekeeping,” he says. He said that 10 years ago, when he attended Colorado state beekeeping meetings, he was “the youngest guy in the room” and the only one under 40. Now, he says younger people are getting interested in the practice.

An All-Natural Adversary

But beekeepers are still experiencing high annual losses. French says this is due in large part to the Varroa destructor mite, which — besides having a name like a comic book villain — is one of the honeybees’ greatest foes.

“It is by far the biggest threat to honeybees […] even more than the pesticides,” he says, echoing Seshadri’s claim that pesticides are more of the go-to scapegoat than the primary bee-killing agent.

“When commercial beekeepers take their bees to farms, remember, those farmers want those bees there,” French says. “They’re paying for them. So spraying things to kill them, sure, unintentionally that does happen. But they’re paying for bees to come there. They want the increase production.”

In other words, if farmers’ crops rely on pollination to increase profits and production, and they’re paying beekeepers for their services, it’s in the farmers’ interest to avoid spraying chemicals that could harm honeybees.

The rise in hobby beekeepers, at least on a theoretical level, is a good thing for the honeybee. But because the mite can easily spread from colony to colony, and beekeepers new to the space might not have the same level of knowledge or time to effectively manage their hives, French worries that an influx of hobbyists may actually increase the Varroa destructor problem.

French describes his treatment plan to halt the mite’s spread as follows: “When I treat my bees, I have some other friends that keep bees in the area. And I always tell them when I’m going to treat and we try and coordinate training. So, we kind of hit the whole area at the same time.”

French has been using some of his hives to study the interaction between honeybees and hemp. And he’s not alone. Seshadri and one of her students, Colton O’Brien, have also been researching hemp and bees to try and set out a plan for responsible pest management in the future. For both parties, the results are promising, although with some substantial caveats.

Hemp & Honeybees

It’s a promise that is repeated often throughout our emergent industry: There’s a hope that hemp can help.

In June of 2015, French set out to test how honeybees and hemp would interact. His hypothesis was that encouraging bees to pollinate a field would encourage seed production for hemp plants.

“When people told me that there was a seed shortage and hemp seed was selling for $10,000 a pound or $10 a seed, I was like, this is easy. This is what beekeepers do. We take our bees, we increase productions, and get output on crops,” he explains. “If I could help increase the seed production by one pound on the field, it definitely over pays for my services.”

French placed 12 hives on 70 acres of hemp being grown for fiber and monitored and reported his results throughout the summer.

“The bees love the pollen. They go crazy for it. But cannabis and hemp are naturally nectar-poor, meaning the plant does not produce a lot of nectar for bees,” he says. Bees require nectar to make honey for food, so as a result of the low nectar amounts in the cannabis, French says the bees “pretty much starved to death” by the end of summer. “They couldn’t produce enough honey to sustain themselves,” he says.

For plants that are wind pollinators, such as wheat, rice, and dandelions, this is normal. For commercial beekeepers that ship the hives around the country for pollination services, it simply means supplementing the bees with food — a practice widely used, but which some blame for poor honeybee health.

In other words, honeybees can help hemp farmers increase production, but the bees can’t live solely on hemp.

However, hemp can play a role in helping pollinators, says Seshadri. Her student O’Brien was working in the field, she says, when he noticed an abundance of wild bees and honeybees on flowering hemp plants. His curiosity piqued, he spoke with Seshadri and they decided to set up a study for the following summer to investigate the relationship between bees and hemp.

Their results yielded evidence of a wide variety of pollinators interacting with the hemp, something encouraging despite the lack of nectar produced.

“Male hemp comes to flower around August or September, which is really a crucial time for a lot of pollinators, because they’re kind of heading towards the end of the season,” she explains.

Despite not getting nectar from hemp plants, bees do harvest pollen, which is protein-rich and essential for larva development. During the late summer months in Colorado, very few plants or crops that provide nutrition are in their flowering stage.

“So that’s what makes hemp really stand out. In Colorado, it fits into the whole agriculture system by providing pollen at that crucial time in the season,” says Seshadri.

For Seshadri, the timeliness of hemp’s flowering stage, combined with the potential of a new crop that we can study before developing pest management strategies, makes the hemp-honeybee relationship an exciting one.

The distinction is, however, that the hemp can’t be feminized in order to provide pollen for the bees. With the unprecedented amount of money flowing into the CBD space post-legalization, it’s a fair bet we’ll see a massive increase in the acreage of hemp planted for CBD this year, which involves female hemp plants producing high-CBD flower instead of male hemp plants releasing pollen.

And therein lies the rub. While hemp and honeybees appear to offer each other something that can be mutually beneficial, if new investment money turns hemp into simply another monoculture crop that isn’t releasing pollen, hemp could be part of the problem for honeybees, not a part of the solution.

When it comes to recognizing and acting on the myriad problems that affect pollinators, the needle is trending in the right way, says Seshadri. But that doesn’t mean we’re in the clear.

“I don’t want anybody to sit back and relax and say, ‘OK, we did our job.’ I don’t want to scare people and say bees are disappearing, but I don’t want to say that everything is okay, just move on,” she says. “I want people to realize that every action we take has a consequence.”

So while there’s hope that hemp can help mitigate some of the issues influencing the honeybee crisis, the plant’s role will be largely a supporting one. Just as a multitude of problems are affecting the bees, like so many legs of a table, a multitude of solutions are needed to save them.

This article was originally published in the print edition of Hemp magazine.